Author’s Note: Hard truths time. Before you go in, some disclaimers about where this is going so you can read it in the right headspace. This isn’t a subtweet blog, but it does vaguely track the relevant discussion of the publishing hour (how an agent rejects you) and my vast experience being rejected by pretty much every agent in this business (including my own at one point). It’s for newer writers and is more relevant to 2023 than not. It’s not particularly positive (or I would argue negative, it’s honest). It’s based on my experiences in both self-publishing and traditional publishing over the past decade, though focuses mainly on traditonal publishing. It can thus be reflective of only one person’s point of view, which as I like to remind folks is white and cisgender. It contains minimal advice except some tricks I’ve seen used and to practice mindfulness and self-care. Finally, I think it’s fair to note that I am (finally) agented, so I do have a rose-colored perspective on querying (sort of, lol).

Content Warnings/Trigger Warnings: Discussion of rejection, loads of it.

Welcome to Publishing, Everything Sort of Sucks Here

I’ll be the first to admit that when I (re)entered the querying trenches in 2017, I was not prepared for what I was about to face.

Neither failure nor rejection were particularly new to me. I was querying on the heels of what I considered two failed self-published books. Those books were rejected by what felt like the world. They had also been specifically rejected by hundreds of bloggers, bookstagrammers, and Goodreads reviewers* who I had to pitch to one by one, according to their varying instructions. Those emails were frequently rejected and ignored. Sometimes, they were accepted, only for me to spend dwindling money on printing and shipping to the result of no review. Once (only once, a victory, honestly!), one was read, resulting in my first one-star review.

Not so unlike querying, truth be told. Except querying never cost me hundreds of dollars.

*(No shade to reviewers, by the way, an honest review is an honest review, and your time is your time! You’re as unpaid as the rest of us, I mention this experience only for a close comparison to the traditional publishing world’s rejection to link the two together).

This is what I told myself as I prepared to query (for real, as an adult) my first novel.

I was ready.

The first of many lies I would tell myself over the next five years.

The Rejections

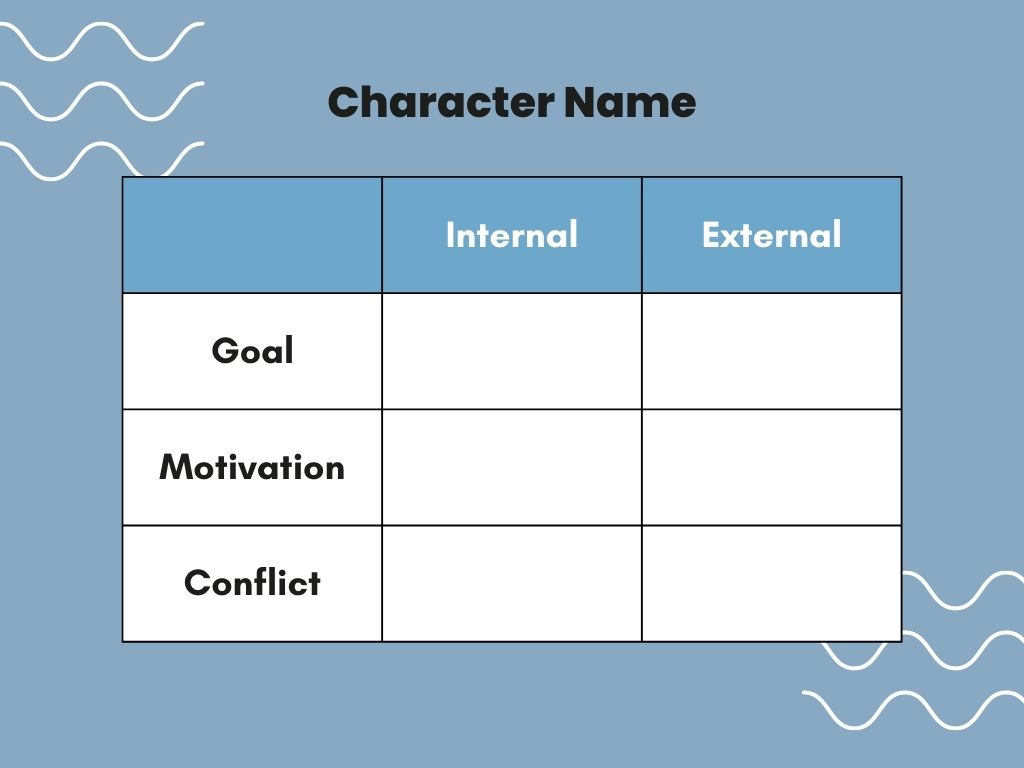

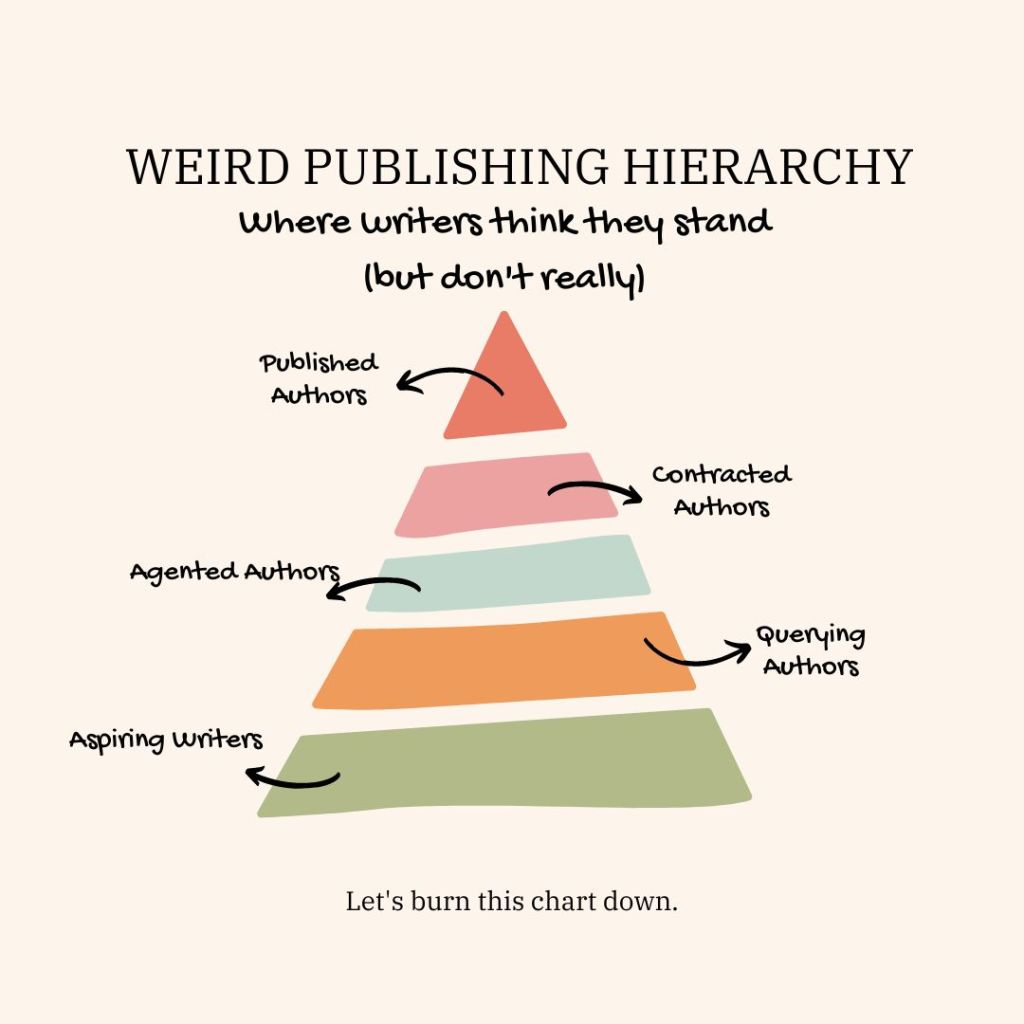

It’s been awhile since I did a nice chart here, so let’s start with one of those then break it down from there.

The Form Rejection

In 2023, the form rejection is the most common type of rejection to receive (besides potentially Closed No Response, more on that at the end of this section). I hear legends this wasn’t always the case, but for me, it sure as shit has been, so I’ll take people at their word when they say that wasn’t true in 2017. (I also hear that a 20% request rate was a perfectly reasonable thing to aspire to in 2017 but again, rocking that big goose egg for years over here, so I’ll have to believe other people when they say that).

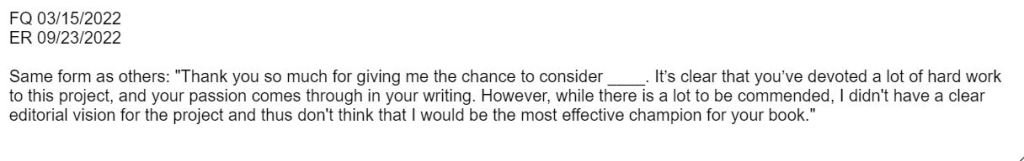

What does the form look like? Well, it depends on the agent. Some agents have forms that say “This is not right for me, but thank you.” Some agents have forms that are so un-formlike I (and others) mistake them for personalized rejections. Some agents have multiple versions of form depending on what (in their mind) went wrong (thanks for submitting this, but I don’t accept this genre versus thanks for submitting, but I didn’t connect the way I’d hoped, for example).

If you’re new to querying and aren’t sure what might be a form, the best way to figure out if you’ve been formed is to go to QueryTracker and read the comments for that agent. Lots of people will record what the form for the agent is or what they believe it to be. If you received the same thing as others, you’ve been formed. Try not to stress, it happens to literally everyone at least ten times (or ten dozen). (If you did not get formed ten times or more, please happy dance elsewhere, this post is not for you).

When I started querying, I hated form rejections. I particularly hated form rejections of the “this isn’t for me, bye” variety. I hated them for all the reasons many new (or newly querying) writers hate them. Because they didn’t give me any information about what was “wrong.” And there’s so very much that can be wrong. The query, the pitch, the idea, the pages, the writing, the genre, me.

What. Was. Wrong.

If I knew what was wrong, I could, presumably, fix it.

Hard truth. A lot of the time, you can’t. I’ve said it before, I’ll say it again. If you’re doing The Things (getting beta reads, critiques, improving your craft, putting together a strong query package, listening to fedback and taking it, etc.) you’re probably doing nothing wrong. You are simply having bad luck.

I also hated them because they felt cold. Some didn’t have my name, or the title of the book. I had no indication if the agent had even read the damn thing.

Hard truth. They are cold. I don’t know these people. They don’t know me. I’m a drop in the bucket. It isn’t personal. Therefore, it doesn’t feel personal. That hurts because it is personal. Here I was, putting all this time and effort into something, no not just something, my dream, and on the other side of a screen someone didn’t even take time to read it! It felt unfair. Unjust. Wrong.

Yeah, there’s that word again. Wrong.

I thought if I could prove to an agent I work harder than everyone else I could show I deserved this more.

Wrong. Wrong. Wrong.

I don’t work harder than everyone else. I work hard. There are people who work harder. I know that without a doubt now. I admire these people. Envy them. Sometimes worry about them. There are people who deserve this more. I feel guilty about that. Frequently. There are better writers than me. People who I feel have stories more worthy of being told. My distinguishing factor is I was determined and lucky. I hope loads of others will be too. Some of them already have been, and I cheered for them harder than anyone.

After I got over myself, of course. Some days I still need reminidng, and humbling, yes. That’s normal. Human. Don’t hate yourself for it, but do try to be better in spite of it. Be kind to yourself when you fail to be better, then try again. Forgive when others around you inevitably fail (and with the exception of a few, most everyone will fail at this along the way).

Anyway, back to rejections.

By year four of querying, I started to prefer form rejections. Better than a no-response. Better than a personalized rejection that made me wonder if the agent liked it why not request? Better than feedback that suited one agent but not another. Forms were tidy. An answer to pilot me to QueryTracker to mark this one closed and move to the next. In and out like a wave.

Also by year four I had (sort of) learned that I wasn’t really doing anything wrong and even if I was, agents weren’t here to teach me about it. I had to learn from other writers, from critiques, from doing the work. But more than anything, I needed the right idea at the right time pitched to the right agent in the right way.

Honestly, it’s shocking it only took five years and four books.

The Personalized Form Rejection

According to the Wisdom that Was, personalized form rejections used to be much more common than they are now. Again, I never saw one until Pitch Wars, but I’ll believe people. They’re not common now. At all. If you get one, celebrate. Believe it or not, this rejection is a victory. It’s the partial request of the new querying era. Someone liked your work enough to spare the time to tell you (even if it’s a line, in this overworked, underpaid industry, a line is money not made so you earned that, celebrate it).

If you’re not sure what a personalized form rejection is, usually it’s the form plus something a little extra specific to your book or pages. Maybe it calls out a character or a particular element of your world the agent thought was interesting or unique. Maybe it’s more generic. I received one for my Pitch Wars book that said, “I definitely remember this one from Pitch Wars!” Then go on to praise my writing and premise.

Personalized rejections are (in today’s market) an indicator that your query and sample pages are “working.” They aren’t a reflection of your work.

Hard truth. They still feel that way.

If there’s one thing that’s true in this business, there’s two. Here are two things to know about publishing and personalized rejections:

- The goal post will keep moving, so celebrate every win as best you can (this is harder than it seems and doesn’t get much easier). When I was in the query trenches, I always seemed to be doing Worse Than Everyone Else. Friends would bemoan their losses and I would envy them for where they were. Must be nice to be sad about a personalized rejection. I’ve never gotten one. Then, one day I got one. Annnnnd was sad about it. Quickly, my bitterness turned to Must be nice to be sad about a partial rejection, I’ve never had a request. Then, one day I got one. Which wasn’t good enough because it wasn’t a full. Which wasn’t good enough because it wasn’t 10 fulls. You see how this escalates. It’s hard. Keeping your eyes on your own paper isn’t really possible with social media or writing friends and you need at least the latter, I’ll be honest. You’re going to compete against your friends, your peers. You’re going to feel these feelings (probably, or maybe I’m the only asshole, but I like to think not). When you do, acknowledge them for what they are, and keep them on the inside or with an extra trusted friend or two. Better, have a friend to call you on your bullshit, gently and with compassion, but honestly. Megan Davidhizar is mine (ps if you like YA thrillers you should totally Add Silent Sister On Goodreads, it’ll blow your mind I should know I read it FIRST and told her then it would be The One which was of course, correct). Megan parrots my own advice and moving goal posts back to me with the memory of an elephant, and the humor of a patient saint. “Oh, look at that, remember when you said LAST TIME this thing then you moved your own goal post? Funny how it becomes impossible to do things.” Okay sure, fine, she’s right. My sincerest wish is you all find a Megan to annoy the shit out of you with the exact right amount of tough love plus validation you need.

- “Near misses” are a thing to seek and destroy from your brain. The concept of a near miss is somehow more haunting than a flat out nope, goodbye. It’s like that partner you break up with not because anyone did anything wrong but something just wasn’t quite “right.” The person you think about every once in awhile, a nagging worm in your brain. You know the one. The one who got away and left you with this whole world of possibility you didn’t explore for reasons that aren’t entirely clear. The one you think about reuniting with on an Oprah episode in some serendipetous act ten years in the future “First Loves Reunited.” After all, it wasn’t bad it just wasn’t right but that could have been fixed, couldn’t it? Nope. That person is not The One. And your book, I’m sorry to say, was not the agent’s The One. There was nothing fixable to make it “right.” Not because it was horribly broken but precisely because it wasn’t. It’s fitting a square peg into a round hole. The square is perfect, the circle is perfect. They just don’t fit. Acknowlege you wrote a great square and you need to find your square hole, and do your best not to let that near miss eat you alive. Easier said than done, I know. Which is why I prefer the form rejection now!

Feedback

All right, I’ll be honest here, I don’t know too much about feedback because I’ve literally only received it one time, and it was from my now-agent on a book they passed on prior to offering on another book. The feedback was lovely, in depth, and kind. It made me want to revise the book, which I did. It resonated the way a CP’s feedback resonates, and was in large part the reason I queried my agent with another book immediately thereafter despite having quit writing forever. Because I know feedback like that from anyone, but especially an agent is rare.

Feedback in a rejection (i.e. not a request to revise and resubmit) can be a bit perilous, however. What one agent dislikes or thinks should be revised isn’t always the same and feedback is so rare these days it’s unlikely you’ll get enough of it to see the same thing repeated often enough for you to say okay yes, this is the market saying I need to revise this, or this is objectively a hole in the craft, or whatever. Revising your book for an agent who didn’t offer on it can change something another agent would have liked. Or, it may change absolutely nothing but waste time you could spend working on a new project. Worse, you’ll never know which it was, so there’s a good chance you’ll end up doing that should I should I not have dance forever more. Or, for awhile, anyway.

The best advice I have on feedback is to take it and run with it only if you know in your gut it will make your book better for you. Not anyone else. You.

The book that my now-agent gave me feedback on? I revised it after I’d shelved it. Because I wanted to see if I could make it better. Because the feedback made me excited to write again. I revised that book one final time for me and no one else. It’s a better book for it. I’m a better writer for it. Revise to make the book better in a way you believe in, and your decision will hopefully be easier to swallow regardless of what happens.

CNR (Closed No Response)

Okay so first, CNR means Closed No Response. It took me more years than I’m willing to admit to learn this, so you’re not alone if you’ve been head scratching.

What it means is the agent didn’t respond to your query. That “No response means no” policy you see on many agent websites these days. Next to the form rejection, the CNR is probably the most common form of rejection these days (maybe more common?). It’s the source of much controversy and despair. I hate it. I’ll never learn to accept it. Well, I could, but the only way I could publishing will never be able to accomplish, so I suspect we can both continue to stubbornly ghost and glare.

The way, you ask? Well, as a neurodiverse individual, I could probably be persuaded to grudgingly accept the CNR as I’ve accepted the other forms of query rejections if it followed rules. The hardest thing for me with the CNR has always been how erratic it is. No response means no except not always. No response means no within 6 weeks not in 2023 though, lolz. No response means no for some agents here but not others but good luck figuring out who.

I’m not faulting agents for this. They’re busy. It takes time to send even a form rejection. Time they don’t have because they’re not getting paid unless they’re selling books. Timelines are impossible to keep. Websites are obnoxious to update, so updates are pushed to the neverending to do list of small business life.

It’s a reality, though. CNRs are hard. And sometimes they aren’t actually CNRs. Rejections you closed out in QueryTracker (and your heart) pursuant to a no response means no policy might come again in a form months later. They sneak out of nowhere and knock you right off that surfboard. Shitty, silent waves.

Hard truth. All you can do is brace yourself for them.

I have a CP who marks every single query CNR in her spreadsheet as soon as she sends it. Something about ticking a box from “mystery void” to “known rejection” makes her feel better than taking an empty box and ticking it to “mystery void” after months of waiting (and potentially getting hit again months after with a form). It makes a certain kind of sense to me, really. It’s killing the hope before it gets a chance to breathe. One of those it can only get better from here kind of tactics.

The Conclusion of Care

In my author’s note, I said this blog doesn’t really have advice. I guess it has some, but I don’t profess to know the secrets for everyone. Different things work for different people. I always recommend setting up a separate query email just for that, then turning the notifications off. I know people who have loved ones take control of their query inbox, filtering out rejections for them. Others who only check the inbox when they have the ability to take on the rejections.

Some people try to find meaning in every form, every word. Some people find solace in research, in trying to perfect the query for every agent. Others say fuck it and send queries to everyone (but never in a blind copy or absolutely not carbon copy sort of way). Some people have to space out rejections by querying in batches of 10-20, others prefer the “bandaid method” as I call it of making the query package as strong as possible, then querying every agent on their list all at once.

I’ve done it all. None of it has made the rejection easier.

At the end of the day, rejection is rejection. Yes, it’s part of the business. Yes, you’re going to face a ton of it. No, I’m not going to preach thick skin because some people can’t do art without access to their skin. Me, for one. My trauma history causes me to disassociate when I’m facing a lot of upset. It helps me work well under pressure when the work I have to do is survive. When the work is logical and practical and decision-centric. It doesn’t help me write. I can’t access the feelings I need to write in that state.

What I need to do in those moments isn’t pull up my bootstraps and keep working. It’s grieve. Sleep. Cry. Scream (in private). Rage. Vent (in private). Then heal. And if and when I’m ready, try again. And again. And again.

Hard truth. Rejection is part of the business. There’s no easy way to do it or receive it. It simply is. Naked, plain, true.

Welcome to publishing, everything sort of sucks here.