Author’s Note: While I write both young adult and adult fantasy, this post will focus on my adult fantasy. Also, I am using the term “women” here to encompass a general target audience in publishing (and to make a snazzy title) but don’t intend this term to be narrowly construed and will use gender neutral language throughout.

My college writing program was highly competitive and well-known. Our school of journalism was equally so. As a consequence, sometime during the fall semester of my sophomore year, I found myself at a Starbucks, sitting across from a 4’11”, journalism major from New York who’d emailed me out of the blue requesting an interview with me for a story she was writing about the creative writing program.

I had no idea this petite girl with a less than petite attitude would become one of my closest friends and future roommate. Honestly, I thought we might not ever see one another again because most of the time we spoke she never took notes, so I assumed she didn’t find me particularly interesting. But when I told her I “used to” write fantasy, she pushed her chai tea to one side and picked up her pen. Apparently that was more interesting than anything else I’d said about the writing program, how it worked, or lit fic.

“Why fantasy?”

It was a question that has followed me ever since. My answer hasn’t really changed, though, even if it has probably become more nuanced.

What I told her then was fantasy gave me a way to address things that mattered to me in a way that didn’t seem so on the nose, something I was constantly getting scolded for in my writing classes when it came to my lit fic. “This isn’t a morality tale, Aimee.” Was a not infrequent comment on my short stories. At the time, I hadn’t learned the subtlety needed to nudge in a real world setting.

Possibly because I’d spent my entire life reading fantasy. Possibly because I sort of hated writing lit fic.

But fantasy gave me that outlet and let me make it as bold as I wanted, because with fantasy the reader is steps removed from the real world. They can disconnect when their ideas are being challenged and come back later. It’s a softer way to influence. A more fun way, too.

What I would add now is that issues can also be targeted and isolated in fantasy. You are the builder of your world. You can throw out some things from our world to focus in on others. (That bit admittedly took me much longer to figure out and is always going to be a work in progress).

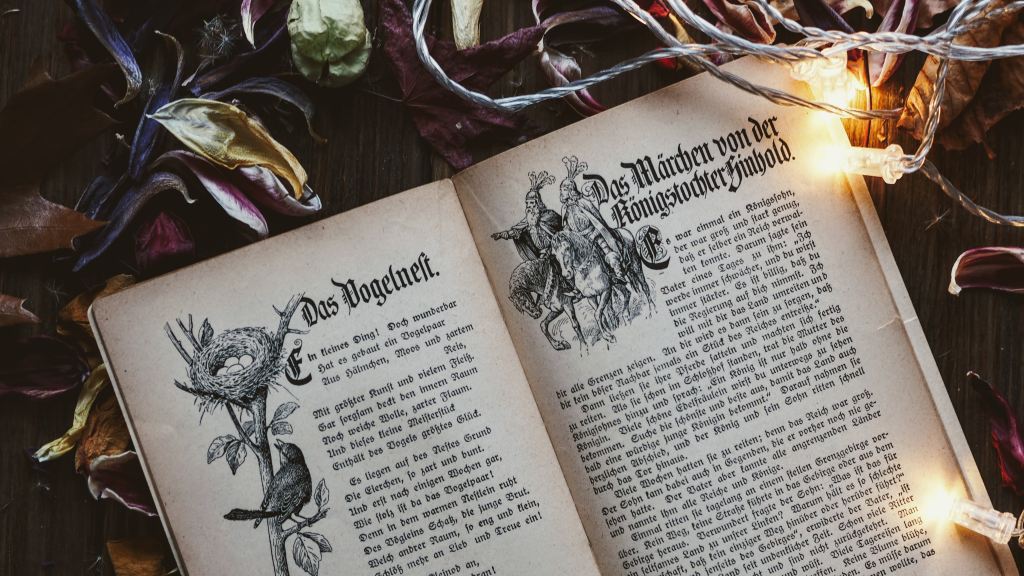

I’ve written before about fairytale retellings and why it’s important we market them to adults and shelve them as fantasy. But while I was in Boston for work last week, I was (naturally) asked about my books, and why I write fairytales for adults.

What a question. A good one. More complicated than you’d think.

It took me back to college. To that question about why fantasy. But also to a comparative literature class I took about fairytales and how they affected the socialization of children across the years. Spoiler: Walt Disney was pretty sexist, and racist, and all the isms, really.

Yet, fairytales have a structure that appeals to me as a neurodiverse individual. Plus, their goal is the same goal I seek in writing, well, anything: Influence. They are quite literally morality tales.

Children aren’t the only ones who need morality, though. Adults do, too. But it’s different. Like the adult life, it’s messier, grayer, more complicated. So what do I do with that? Well, I take the structure of a fairytale and I bend it, twist it. As my Pitch Wars mentor would say, I often fracture it.

After all, it’s only when something has been broken that it can be put back together.

Main Components of a Fairytale

Characters

There are three main types of characters in fairytales: goodies, baddies, and allies. The main character “goodie” is typically young, poor, unhappy, and “pure.” They’re likeable. The one you’re rooting for. The Disney Princesses. The baddie is usually the direct opposite of the goodie. They’re often old, rich, miserable, and “evil.” Often, they’ve stolen from the goodie and intend to keep that just how it is, thanks. The wicked stepmothers and vain witches. Then there’s the allies. The allies are across the board in fairytales. Sometimes they’re animals, sometimes they’re friends, sometimes they’re love interests. Dwarves, princes, helpful mice, a well-placed good witch. The baddies have allies too. Flying monkeys come immediately to mind.

You know what I’m on about, right? There are really neat formulas here. We as readers like the goodies and dislike the baddies. There’s not much gray area, so down the yellow brick road we go.

I mean, unless you’re reading one of my fairytales. Then you might not actually know who’s a goodie or a baddie and the traditional roles might not be what you expect. Because that’s life, right? Sometimes we don’t know who to trust and… oh, I’m spelling out my moral again. Guess you’ll have to read the books someday!

Magic

Fairytales have loads of magic. Not only magic systems with evil (and good) witches but also magic numbers (3 and 7 are big ones). And, of course, magical creatures. This puts fairytales in the fantasy genre.

My magic systems are often based on morality concepts I want to explore. What is selfishness? What is really selfless? What happens when the goodie wants to be a baddie? And what makes a baddie a baddie, anyway? They also often deal with power. Who has it, who wants it, and what it takes to get it.

Obstacles or Tasks

The basic structure of a fairytale requires the goodie to overcome tasks or obstacles that often feel or seem insurmountable to reach their happily ever after. Usually they need magic and allies to accomplish these tasks plus one of their handy and winning traits that makes us love them, like courage or cleverness.

Most stories have obstacles or tasks, if we’re being honest. My fairytales are no different. The tasks are just more adult than in a traditional fairytale. Because they’re for adults! Don’t fall in love with this guy even though he’s sexy. Do this job even though you hate it. Kill this dude so you can reclaim your position. You know, normal life stuff.

Happily Ever After

Most fairytales have a happily ever after BUT NOT ALL. Especially in older tales, this was not as much of a genre convention as it came to be. Depending on your definition of happily ever after, you might see this differently, too. If you’re like my partner and have a taste for dark justice, you might see the version of Snow White where the wicked queen is made to dance wearing red-hot iron shoes until she dies as a suitably happy ending. But probably few see The Little Mermaid telling where the prince marries someone else and the Little Mermaid throws herself into the sea, turning into foam as an HEA.

Today’s fairytales, however, do typically require a happily ever after. Mine have them, but they’re never what you expect. #LitFicTaughtMeThat

The Moral Lesson

This is probably the biggest concept in a fairytale, and the reason I love them as a medium for retelling. Fairytales teach the morals of the time period in which they’re told. It’s why they’re told and retold again and again. It’s why we don’t tell the version of Snow White with the dancing on hot iron shoes, or the version of Sleeping Beauty where she isn’t woken by a chaste kiss but by the kicking of her babies because–surprise!–she’s been sexually assaulted in her sleep. It’s why the new live versions of Disney feature a Princess Jasmine who wants to be a Sultan, and a Black Little Mermaid. It’s why our new fairytales expand to a Queen who loves her sister and is ultimately rescued by her, not a prince; a Polynesian “Daughter of a Chief who isn’t a Princess;” a demi god who self-corrects he’s a hero of men, no women, no all; a Colombian family who is magical but traumatized; and a Mexican boy who wants to chase his dream of playing music.

My tales have moral lessons, too. For the millennial primarily. Things we didn’t get in our versions of Disney. But also things that are important to us now, as adults navigating a world that, in many ways, is different than the one we were prepared for.

I joke that my brand of adult fantasy is “fairytale retellings for women with work issues” because I primarily write retellings centered on women who have some kind of issue with work. All Her Wishes is about a fairy godmother who hates her job. My current retelling is a genderbent Beauty & the Beast about a sorceress who is pissed about a promotion gone all sorts of sideways.

At their hearts, though, my books aren’t really only about work, or even mostly about work. They’re about finding your power and your place in the world. My books have morals, but not the ones I grew up with. Ones I’ve learned along the way. And the thing is, while it might be children are easier to influence, they’re not the only ones who need influencing.

I guess in the end, I ignored those comments about morality tales.