Author’s Note: First, sorry I’ve been a bit MIA, things at the 9-5 have been hectic! Now, about the following blog: To be totally candid it was originally drafted in a moment of late night, desperate sadness that turned to fury. I’ve subsequently edited it, pulling back on fury to add what I hope comes across as tongue-in-cheek humor at the forefront before asking what I intend to be genuine discussion questions about the lens through which we view not only Adult SFF but literature in general. This piece is primarily about internalized sexism but also touches on race and other marginalized identities. I caveat that I’m female and neurodiverse but not a monolith. I’m also white. This not an attempt to speak on behalf of voices that are not my own but instead to recognize them. Wherever I use the word “woman” please understand this to include trans women and anyone who identifies with or as a woman at any time, including but not limited to nonbinary and gender fluid folks (if there’s a wish to be included!)

To the extent the argument you might put forward in defense of the alleged “dumbing down of fantasy” trend is due to a flood of white women authors entering the market, I make no argument contrary to the actual facts. Those are that the market continues to be depressingly white. I do intend to argue, however, that any argument that women writers of any race or color who include love, romance, sex, or less traditionally “intense” topics in their Adult SFF somehow leads to the “dumbing down of fantasy” begs a critical re-examination for potential internalized sexism. This point is not expressly stated in the piece as I attempt instead to pose questions for consideration, but I don’t want it to go misunderstood or my position on this issue misstated.

TW/CWs: Opaque references to internalized ableism, sexism, racism. Quote from Moby Dick containing offensive language relating to Indigenous Americans and those of Persian descent.

Length Warning: This uh… got out of control. Apologies and congratulations to anyone who makes it through.

pe·dan·tic

/pəˈdan(t)ik/

adjective

of or like a pedant.

An insulting word used to describe someone who annoys others by correcting small errors, caring too much about minor details, or emphasizing their own expertise in some narrow or boring subject matter.

Merriam-Webster online

I don’t think this word means what people think it means.

I’ve seen it bandied about a few times lately, mostly to describe a trend in Adult SFF toward publishing books that are more accessible to different groups of readers. As in, “I’m so sick of books that read too YA with their pedantic dialogue.” Or, “Can’t anyone read anymore? All these books are so short. In my day, we all read 350,000 word Robert Jordan books in one sitting and waited eagerly for the next!” Or, “My hot take opinion is adult SFF these days is being dumbed down by this trend toward a certain type of book.” Certain type. Yeah. Avoid the comments to those ones if you: (1) know what they’re hinting at; (2) disagree; and (3) are near breakable things.

Good old fashioned elitism, right? How you never cease to amaze me with your inability to do a google. Who needs to google when there’s yelling on Twitter, eh? It’s not like you’re making a hugely elitist literary argument in favor of the “smart” side while using language incorrectly or anything, psh! What a nitpick. To correct you might be well… pedantic.

That Trend, Those Arguments, My oh My

While we’re here, let’s talk about that trend and those arguments.

First, call the spade the spade. The trend is romantasy. Maybe cozy fantasy, too. The argument can be couched however people want to spin it, but here are some of fantasy’s most favorite hate hits: books with protagonists (don’t you know they’re almost always women) who are too “voicey” and/or “immature”; authors who use prose that’s too simple or “commercial” (the calamity! being commercial in business-to-consumer commerce!); authors who don’t write “beautifully”; stories that “feel too YA” (I know you’re shocked to learn it’s female protagonists targeted here, too); short books that “dumb down the genre” (it’s almost like authors are aware of the cost of paper and the demands of their target market or something…), and not a small number of other similar things.

If it walks like a duck and talks like a duck it’s probably a duck.

The argument is elitism. Sexist elitism. My favorite kind.

I’m putting the YA feel and voice/immaturity arguments aside for another day lest this blog become a thesis paper. Instead, I’ll focus on the prose concepts and how we determine what makes a book “smart” or “one of the greats” versus one that apparently single-handedly and without ceremony seeks to destroy via stupidity not only several hundred (arguably thousand) years of sacred literature but quite possibly an entire society. I mean honestly, what’s next? First they canceled cursive, now 500 page tomes, where will it end?

Prose (Pedantic or Otherwise)

What constitutes beautiful prose is subjective, that’s what makes writing art. However, you’ll find in elitist circles *coughlitficcough* there’s certain base criteria for beauty or at the very least what constitutes “great” literature. Can you argue over its meaning? Does it have an ending or passage that leaves you looking like Rodin’s The Thinker? Can you take a single paragraph and dissect it word by word, puzzling over each? Is there a whole curriculum to be spun over a sentence? Has it “stood the test of time” (aka is the author usually white, male, and dead)? If yes to a few of these, take a deep breath and sit down, because you might just be in the presence of greatness.

Ambiguous Prose, Generally

George Bernard Shaw (another dead white dude) famously said, “Youth is wasted on the young.” He’s not wrong. Because if in my youth I’d possessed the self-awareness (and courage) I have now, I would’ve pushed back against some of the elitism drilled into me during my “classic” writing education. Not to say there’s anything wrong with ambiguity1 necessarily but putting it on the pedastal I’ve seen it placed on feels more ableist now that I’m self-aware enough to process the gut feelings I experienced in my younger years.

1To not be ambiguous myself, I note here I’m using this word very colloquially. When I say ambiguity or ambiguous prose I mean, generally, language or plot devices found most notably in works of literary fiction where the reader is left to question authorial intent and in many cases, concepts of sociology, philosophy, or morality. More plainly, I’m referring to every book you’ve ever read in an English class that contained some kind of discussion around, “What do you think was meant by [insert word, sentence, plot point, etc.].”

I always hated Chekhov, for example. I hated his vapid, fragile women who seemed to me to be more objects to move around than real, fully-developed characters. I hated his burly, abusive men with their cheating and dishonor. I even hated that stupid little dog in his story “The Lady with the Dog.” Even now, my nose wrinkles and my tongue curls back in my throat. The neurodiversity in me rages against the grayness of it, the injustice, the lack of resolution or seeming point. Yet my professors lauded this man with his characters’ moral ambiguity and enigmatic existences. So much to analyze! Not for me. Nope me on out, please.

Short but Still Cryptic Prose

I once sat through a ninety-minute writing workshop where the professor and 11 students discussed and debated a single chapter of Hemingway, including spending twenty minutes on one sentence I used to swear described a character putting a worm on a hook. The used to is important. You see, when I started writing this post, I was sure the book I remembered was The Sun Also Rises. My college copy is still in my possession. So, after I failed to find my so vividly remembered worm sentence via Google, a thing I do to doublecheck my work, (sidenote, Hemingway wrote about fishing a lot), I pulled that book off my shelf. I’ve now read the infamous “fishing chapter” in The Sun Also Rises (Chapter XII if you’re interested) a few times and haven’t located my remembered sentence.

What can I say? Memory is fickle.

If someone remembers a particularly vivid singular sentence from Hemingway (perhaps a short story?) involving a worm (or maybe a cricket?) being put on a hook, please hep me alleviate this brain worm (ha) I’ve now obtained by leaving me a comment!

While I didn’t find my worm, I did find a three word sentence I’d highlighted. “Like Henry’s bicycle.” Next to it, I’d written, “Henry James – was he gay or a bachelor? Maybe a wound?” I guarantee you I did not come up with this “interpretation.” It was most assuredly fed to me by my professor.

Three words about a bicycle and this is where we go. So worm or no, I still have some questions about how we determine greatness or beauty or meaning. Is this truly deeper meaning or could it be pretty-sounding (arguable on the pretty) gibberish we’ve not only been instructed to read into but also on what the interpretation should be? Am I simply a jaded author too stupid to put deep meaning into phrases like this, or have we all been duped? More importantly, does it matter one way or the other if considering the question causes us to think critically?

For the last question, I’ll insert my own opinion. No. It doesn’t matter, with one caveat. Yes, think! Scorn interpretive meaning! Ascribe meaning! However, I caution you not to claim superiority whether you favor ambiguity or clarity. Because honestly, that’s what people are doing when they say this book is “a great” and that one is “trash” or they say “these types of books degrade literature.” They’re claiming superiority by saying there’s a right way to think and read and enjoy literature and that way is theirs and all others are wrong and thus, inferior.

For sale: baby shoes, never worn.

Author unknown

Purple Prose: Hidden meaning, hidden beauty, or cover up?

What about lush prose, then? You know, the stuff if I wrote it would be cut and critiqued for being “purple.” Writing that really can wander into pendantic territory.

Where prose is concerned, size doesn’t seem to matter. Six words or six thousand, I’ve sat in a workshop somewhere and listened to a professor gush about it. As long as there’s something to analyze! Pages on pages and hours on hours on the meaning behind the whiteness of Herman Melville’s whale without hardly a period or breath to separate it all, and do not get me started on Ulysses.

Then, I didn’t question. Now, I’m left wondering.

Who gets to decide what makes something great or beautiful or smart or meaningful? Agents, editors, critics, scholars, readers? And does that apply to now or later? Is there a yes, maybe, never scale? Who makes that? Does the political relevancy of a 200 year old word make it great today? And is it thus more great than something politically relevant in its own time? What’s more important? Age or relevancy?

Now, as a reader, a consumer, a purchaser with the buying power who thus has the ability to influence trends, think for yourself. How does this line of questioning, wherever your answers may have led you, impact what you buy? Is it helping influence a change in literature or keeping it stagnant? Is the change, if any, positive or negative? Does it affect marginalized voices?

Most importantly, though, is it making you a happier reader and a happier human?

As to my opinion? If neurodiversity has taught me anything it’s taught me that brains are as varied and vibrant as art itself. Different brains require different things to spark them. The difference, the variance, the kaleidoscope of culture and thought and concept is what we should celebrate. Not more… well, whiteness.

I’m different. I like different, and I’m really ready for an Adult SFF shelf with more than the same 15 names on it.

“…the innocence of brides, the benignity of age; though among the Red Men of America the giving of the white belt of wampum was the deepest pledge of honor; though in many climes, whiteness typifies the majesty of Justice in the ermine of the Judge, and contributes to the daily state of kings and queens drawn by milk-white steeds; though even in the higher mysteries of the most august religions it has been made the symbol of the divine spotlessness and power; by the Persian fire worshippers, the white forked flame being held the holiest on the altar; and in the Greek mythologies, Great Jove himself being made incarnate in a snow-white bull…”

Herman Melville, Moby Dick

Bringing it Back to Fantasy

The Time Testament: Aka the “Back in My Day” Conundrum

And now, we address head on the great forefathers of fantasy.

When I was a wee baby writer churning out horrible drafts of fantasy novels with talking Pegacorns and super-powered, teenage mages who had raging hormones and daddy issues for days, I ran into an issue with my reading. I ran out of reading. For the youths, these were the olden times where YA fantasy was not yet a thing, and fantasy books for teenagers, especially girls in love with love, like myself, weren’t plentiful like they are today.

I’d burned through all the Tamora Pierce and Mercedes Lackey and Anne McCaffrey and Kate Elliott and Elizabeth Haydon. Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials trilogy was a weekend job. I’d read all the one-off retellings I could find: Confessions of An Ugly Stepsister; Wicked; Ella Enchanted. I’d dabbled with Libba Bray and her fantasy fiction. I’d read all the “classics” from Tolkien to C.S. Lewis.

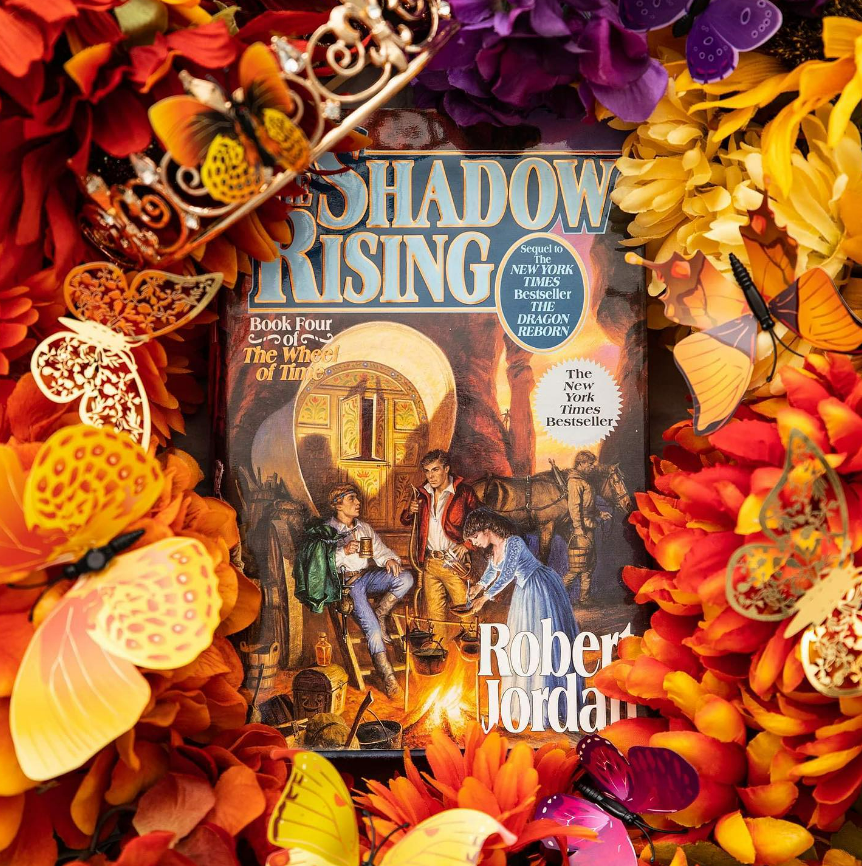

Then, one fateful day, someone, a boy, naturally, told me if I wanted to be a “real” fantasy author I would have to read Robert Jordan’s Wheel of Time series. Because I was young, and unwise, and lacking in confidence, I believed this boy (and others like him) and continued to do so for the next very miserable decade or more. Dutifully but spitefully, I trod through every last word of that series. At some point, I caught up to Jordan’s releasing, and was given reprieves between books. Unfortunately, other boys came to tell me what a “real” fantasy author looked like (spoiler, not me). I was plied with one miserable recommendation after another, then taunted mercilessly when I expressed the tiniest dissatisfaction with the “masters.”

“What a girl!” “You’ll never be a fantasy author!” “You can’t even remember the lineage? This isn’t hard. Are you stupid?” “Poser.” “Fake fantasy fan.” “You’re only here to chase dick.” “She doesn’t even play D&D!” “What, not enough kissing for you? Get a romance novel. This is serious writing.”

High school to college. My days of writing about Pegacorns and escaping into grand quests with talking animals, best friends, and beautiful castles were over. Killed by the steady thrum of turning pages. Pages that sounded like boots. The boots of the (mostly) dead masters come to school me. Rothfuss. Jordan. Sanderson. Lovecraft. Vance. Wells. Brooks. Pratchett. Adams. Scott Card. Vonnegut. Bradbury. Verne. Clarke. On and on and on it went for years.

These books had stood the test of time. Their authors were widely deemed masters of their craft. If I didn’t like any of them, what did that say about me?

Maybe it said I would never be a real fantasy author after all.

Then, I fretted I was defective somehow. Now, I wonder: is a novel “a great” simply because it lasted? If so, what does that mean for the future exactly? What should we be telling young authors about the so-called masters? Do we tell them to replicate this alleged greatness? Nod to it respectfully? Or do we tell them to ignore them entirely and chart their own path? To own the genre and shape it for themselves?

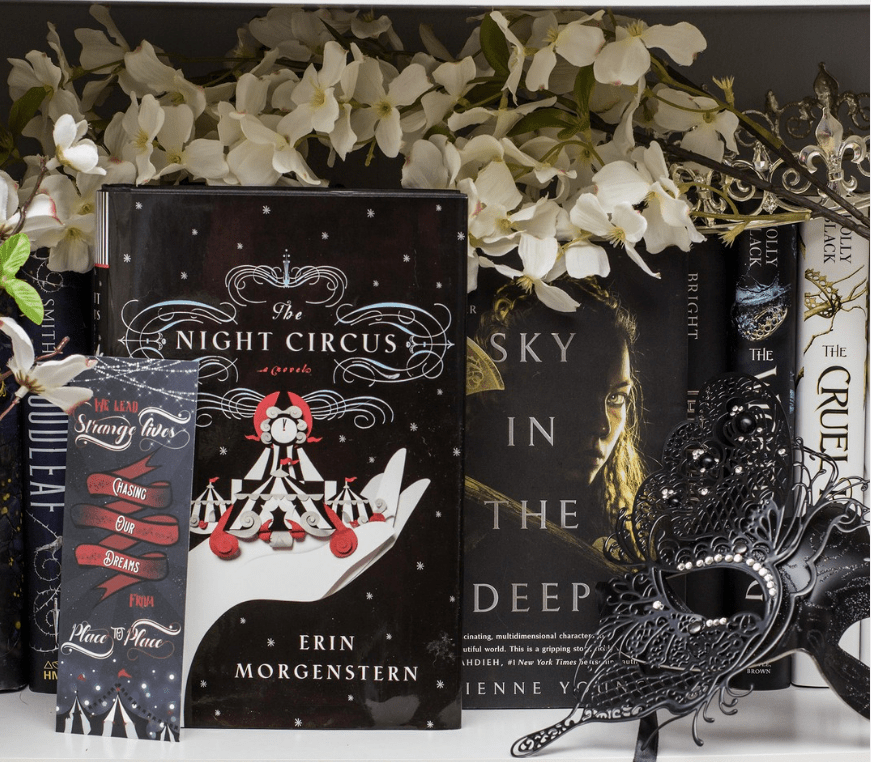

Do we put fantasy elitism on the tower of Tolkien, who spends paragraphs upon paragraphs describing architecture and flies a banner atop “and behold!” or do we look to modern literary fantasy works like Erin Morgenstern’s The Night Circus? If the latter, do we have room to both admire heartbreaking passages you can pluck from the spine and to acknowledge its containment of the usual despised and oh-so-YA insta-love? Can we dissect that work (and ourselves) with a critical but current eye, demanding to know what sets its brand of “immature” insta-love apart from other works being denigrated for dumbing down fantasy?

You may tell a tale that takes up residence in someone’s soul, becomes their blood and self and purpose. That tale will move them and drive them and who knows that they might do because of it, because of your words. That is your role, your gift.

Erin Morgenstern, The Night Circus

TL;DR: Write for You First

Really, though, it’s far past time for authors to take—and be granted—the ability to simply say, I write genre fiction. I write to entertain. I write to try to provide a living for myself and my family. I write to please Netflix. (#goals) I write to make people smile and walk away with a happy sigh. I can and do create art that contains multitudes. Those multitudes include people-pleasing and bringing joy. I write stories about magic and adventure and escapism and yes, romance. I write about other things, too, but full stop I do not have to “prove” I belong here by saying, “I write romantasy, but it has trauma!” or, “I write fairytale retellings, but they take a serious look at systemic, real-world power dynamics!”

I belong here. You belong here. Whoever you are. Whatever fantasy you’re writing. Grimdark. Political. Romantasy. Serious. Literary. Mysterious. Cozy. Sweeping. Epic. Contemporary. Urban. Second World or Portal. Entertaining. Hilarious. Fun. Smutty. It’s all making me better to have experienced it, and if it doesn’t, I stop reading. I’m an adult. This is Adult SFF. I can stop if I want.

And really, does art require grandiosity? Deep meaning? To be smarter than the other book? Better yet, what is something grand or meaningful or smart? If you ask me, making people smile is pretty grand. It also has a pretty deep meaning. Those things are pretty smart. If you don’t know why, consider this my #litficmoment and feel free to analyze authorial intent.

I’ve said it once, I’ll say it again. There should be room for everyone at the table. If you don’t see it, imagine. Then fight for it.

This is fantasy, after all. This is what we do. Dream and do battle.