Author’s Note: This is the Part 2 I mentioned in my last post. The doozy of all doozies when it comes to trauma and dealing with it sensitively. I’ve spent A LOT of time thinking on this topic. It is, after all, one of the main themes of the darkest book of my heart. It’s also a theme of my life. But it’s not an easy subject to tackle because it involves unpacking truths and myths about people just like me. Maybe about me, too. Necessary work is never easy.

As always, I remind my readers what follows is my opinion only, subject to bias and change, wrongness and flaws. I write (and read) through the western lens of American traditional book publishing. While I have C-PTSD, AuDHD, and touch aversion, I’m not a monolith and cannot speak to experiences besides my own. I don’t intend this to be definitive advice or an opinion representing the whole of any group, nor to be extrapolated beyond the groups described.

CW/TW: Discussion of trauma, mass murder, serial killing, etc. no graphic on page description; discussion of some of these themes and issues in history, literature, and film. Some violent imagery in photo form.

Hurt people hurt people.

Source unknown; earliest recorded source, Charles Eads, 1959, Amarillo-Globe Times.

The History of Hurt People Hurt people

In my last post on trauma tropes in narrative fiction, I discussed the definition of tropes. I won’t recreate that wheel here where you can read it there. Instead, I want to talk about the history of this curious, clever, corrupting little phrase. Hurt people hurt people.

As mentioned above, the source of the phrase is really unknown. The earliest recorded instance of it being used is by a man named Charles Eads in 1959 in a review in the Amarillo-Globe Times but there’s evidence to suggest he heard it from someone else, who maybe heard it from someone else, and back and back it goes.

The phrase itself became part of the American mainstream in the early 1990s when several self-help writers picked it back up, including a Christian family therapist named Sandra D. Wilson, who wrote a book with the same title in 1993.

However, the concept of the phrase didn’t have the sebatical the phrase did. Throughout the 70s and 80s, the US was rocked by wave after wave of notorious serial killers. Men like Dennis Rader (the BTK Killer), Ted Bundy, John Wayne Gacy, Sam Little, Jeffrey Dahmer, and David Berkowitz (the Son of Sam) stole life after life with little explanation.

The country wanted answers. They wanted assurances. In all the instability, people wanted to know why these men went beyond murder. The police could answer who, how, what, where, and when. Those things weren’t what people wanted, though. Not when it was over and the bad guy was behind bars. Then, when they felt safe again, people wanted to know one more thing. Why. Psychiatry rose to the occasion, ready with its answer.

Hurt people hurt people.

Before sitting down to write this post, I spent some time learning about the history behind this phrase. During that research, I learned about a psychiatrist named Dorothy Otnow Lewis whose research “with” (or on) violent juveniles led her to testifying on behalf of some of the most infamous serial killers.

Not guilty by reason of insanity.

Lewis’ research (which can be summarized by her in her own words in HBO’s documentary Crazy, Not Insane), indicated that most serial killers shared two things in common: (1) Childhood trauma (being abused or witnessing abuse); and (2) a neurological “issue*” (dissociative identity disorder, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, depression, autism, etc.).

*What is really being said here is someone who is neurodiverse but that word is not always adopted by modern psychiatry and certainly wasn’t when Lewis was doing her work. For this post, I will use neurodiverse but mention this so you can see the hurt even in the definition described. “Issue” I have an issue with.

Why do serial killers do the psychotic things they do? Because hurt (neurodiverse) people hurt people, that’s why.

It wasn’t immediately clear to me from watching the documentary whether Ms. Lewis believes dissociative identity disorder (formerly called multiple-personality disorder), could in fact be a symptom of trauma. It wasn’t clear to me what she thought might be caused by trauma (besides killing people, I suppose). Could all the types of neurodiversity she discussed be a syptom of trauma? A side effect of the brain being broken so young? Schizophrenia. Bipolar. Autism. What can be made by trauma? The film left me wondering if any or even all the things rattling against a broken brain could trace back to the same source: childhood trauma. I’m not sure anyone knows the answer to that at present. If they do, I’d sure like to find out for myself.

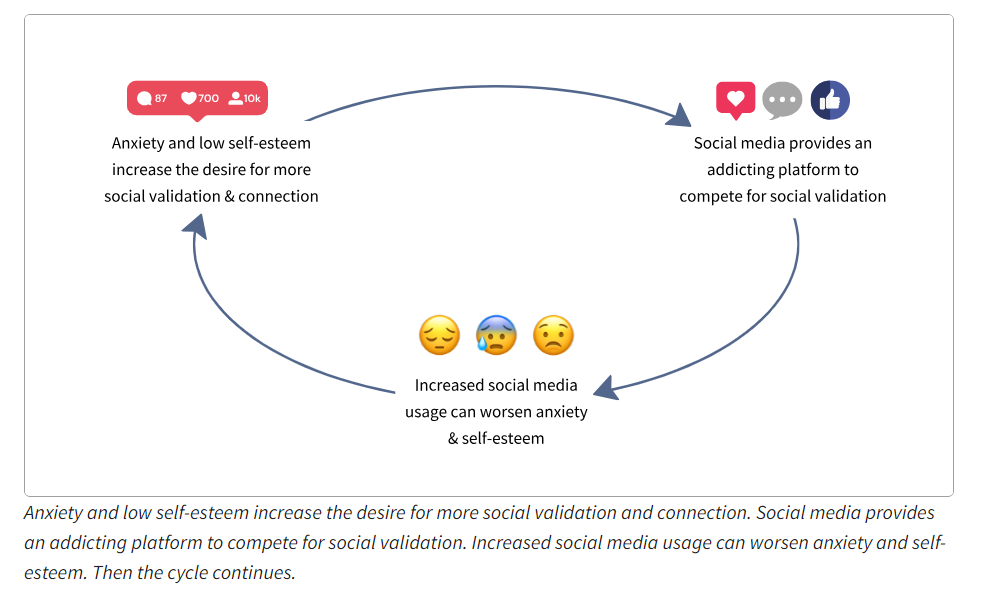

Those whys didn’t matter to the public, though, nor do they for most of you, dear readers. They might not have mattered or even been pondered upon by Ms. Lewis. They matter greatly to me, but that’s a different unpacking not meant for here. What’s important is this hypothesis that hurt people hurt people (regardless of how the hurt manifests) never stopped snaking its way through society.

Which is how it found its way to literature, film, and me.

How ‘Hurt People Hurts People’ Hurts People

It’s probably not hard to figure out why we shouldn’t assume every neurodiverse person with childhood trauma will become a serial killer. Anyone who has seen Minority Report or read a dystopian novel about robots stopping crime before it starts can spot where that story goes wrong. The more difficult topics to address are the more subtle takes on this tale.

Should we suspect a hurt person will hurt us? Might it be safer for everyone to approach with caution someone who might, at any moment, become a mirror of their own monster? These questions roll around in my head day in and day out. Because when you’re a survivor of childhood abuse, you’re often someone who was hurt by someone else who was also hurt. Your abuser is frequently also a victim. In some ways, you can’t be the innocent, unsuspecting victim of a monster. Not when you can empathize so completely with the monster. When you have walked a day in their shoes. Not when their rage runs through your blood as well, an ever present whisper against your skull.

Not like them. Not like them. Not like them.

In modern day media, it’s not serial killers who take the front page, but mass murderers. But today we aren’t focused as much on the why these people (usually young, white, straight men just like serial killers) did it. We’re busying defending why the guns didn’t. “I think that mental health is your problem here,” Donald Trump said after a man killed 26 churchgoers in 2017. Mental health. Many hundreds of diagnoses in the voluminous DSM swept into a soundbite.

And maybe mental health plays a role. But what exactly about mental health? Dr. Michael Stone, a forensic psychiatrist at Columbia, maintains a database that shows 1 out of 5 mass murderers are psychotic or delusional (versus the national population where this is only about 1%). Reserachers at the DOJ have found that almost half have ADHD.

It’s easy to study people in cages, though. Or people who can no longer speak for themselves. It’s harder to study those of us living in the real world. Hell, it’s nearly impossible to get statistics on so many of us because women are so often underdiagnosed and misdiagnosed, and men are so often afraid to seek help at all.

Simple answers, then. That will keep the normal people safe. Not gun control for the whole country. Not less stigma on mental health so more people seek treatment. Not healthcare reform that actually gives people real outlets to real therpaists and psychiatrists. Take the guns out of the hands of the crazies, not ours. That will fix it. Anyone who has been hospitalized for a psychiatric condition should be on the government’s list. Watch them. Group them together and strip them of rights given to other citizens. Surveil them.

When do they start caging us? I wonder every time a new tragedy unfolds on the TV screen and the debate turns once again to mental health instead of weapons of war being available to everyone with an ID and access to a Wal-mart. Every time I read a dystopian novel and have to put it down because it looks a little bit too much like home. Every time I read a fantasy where the heroes walk away from horrendous battles with physical scars but no mental ones yet the villains monologue about their terrible childhoods as a way to humanize not them but the person about to stick a blade through their chest. Of course they became this. It’s a mercy to put them down, really. What a hero.

Don’t give them a choice at controlling their own redemption.

It’s no surprise I’ve always related more to well-written villains than heroes, I suppose.

And I wonder… what does it do to someone to relate more often with villains than heroes? What are we saying to those who have that whisper against their ear and rage in their blood that no matter what we do we will fail? That we are just as we were made to be? Without choice or voice. A foil to those better and more deserving than us. Someone to prop them up.

Not like them. Not like them. Not like them.

Oh, these stories tell us, but you are. You have no choice but to be. And what a wonder it is, to be relieved of that thing ripped from you so long ago. What a burden choice is. How easy it is to surrender it. Even now…

How to Not Hurt People Who are Hurt

This part is tricky, because avoiding the representation erases us, but trauma has a generational component. Hurt people don’t get hurt on their own. Not usually. And the people who hurt them, well, it’s true they were most usually victims once.

I’ve struggled with this my whole life. How to make it real but not messy.

You can’t.

The truth is, trauma is nothing if not messy. Hurt people do sometimes hurt people. Maybe more often than not. It’s hard to say when the statistics focus on the fantastic, and people in cages easily studied and not people in the real world, simply living. People who are often afraid to seek help because they know what the world thinks of them. That said, it’s not entirely wrong to be without caution. Trauma has taught me many things, but that most of all. Vigilance.

But for every serial killer and mass murderer out there, there are many dozens more hurt people breaking the generational rules. One thing I’ve always loved about animal rescue is that it’s a place where you’ll find people like this. Almost without fail. People who once needed rescuing now doing the rescuing. You’ll find them working jobs as teachers, therapists, mental health counselors, nurses, doctors, and yes, psychiatrists. People rewriting their own stories, reclaiming their own voices. Hurt people becoming heroes. Who channel their hurt into helping.

They deserve their stories told, too. Kids who have only ever seen the monsters society makes us deserve to see not the terror in choice, but the beauty. Not in bright, shiny glory earned by people they will never relate to, but in monsters like them. They deserve to see how anger can be molded into a force for good, not evil. How power can be seized, then wielded with empathy. They deserve to see stories where the hero is sometimes the villain and the villain can sometimes be redeemed. They deserve to see stories where the hero isn’t perfect. Where they are hurt. Just like them.

So my advice if you’re going to depict this: Leave the messy versions to those of us living in those skins, asking the deep and tangled whys every day. Living in vigilance and monstrous skin. Let us fight our battles and show them on page. However messy they may be.

For you, don’t erase us, but stop making us your monsters, your villains, your people to shy away from, your morality tales. Instead, consider giving us new narratives. The one we need to seep into society to overtake the old.

Hurt people help people.