Author’s Note: This post is a more practical, craft-based post that relates to my recent post on character agency and trauma. After writing that post, I realized I had some practical application things I wanted to add that might be better as a separate post, so here it is!

Disclaimer: As with my previous post, please note that this is about writing for traditional publishing and any discussion regarding trauma is written from my lens as a white, cis, American writing within that storytelling framework. Please also note this post is about GMC as an author with C-PTSD/trauma not necessarily always about writing characters who have trauma.

During Pitch Wars, while most of my peers were reading Save the Cat! Writes a Novel and Story Genius and working on beat sheets, my mentor had me read a 26 year old craft book by Debra Dixon called GMC: Goal, Motivation, and Conflict: The Building Blocks of Good Fiction.

I loved it. It felt like finally there was a book explaining to me in simple terms the things other people intrinsically seemed to understand about character. For years, I’d tried to revise to advice about goals and agency and active protagonists that was either too complicated or too simple. Now, here was someone to explain what I was doing wrong. The trick is that having an active protagonist with agency isn’t just about having a character with a goal who does stuff. It’s having a character with a goal who does stuff to drive the plot forward. Having a goal of “Get home to eat some soup”* while it’s a goal the character might take action on doesn’t drive the plot forward.

*Actual example from the draft of my Pitch Wars book my mentor saw, by the way. Listen, someone told me the cure to a passive protagonist was to give them goals even if they were small. Turns out, this is not to be literally interpreted. The goal can be small but only if it moves the plot forward.

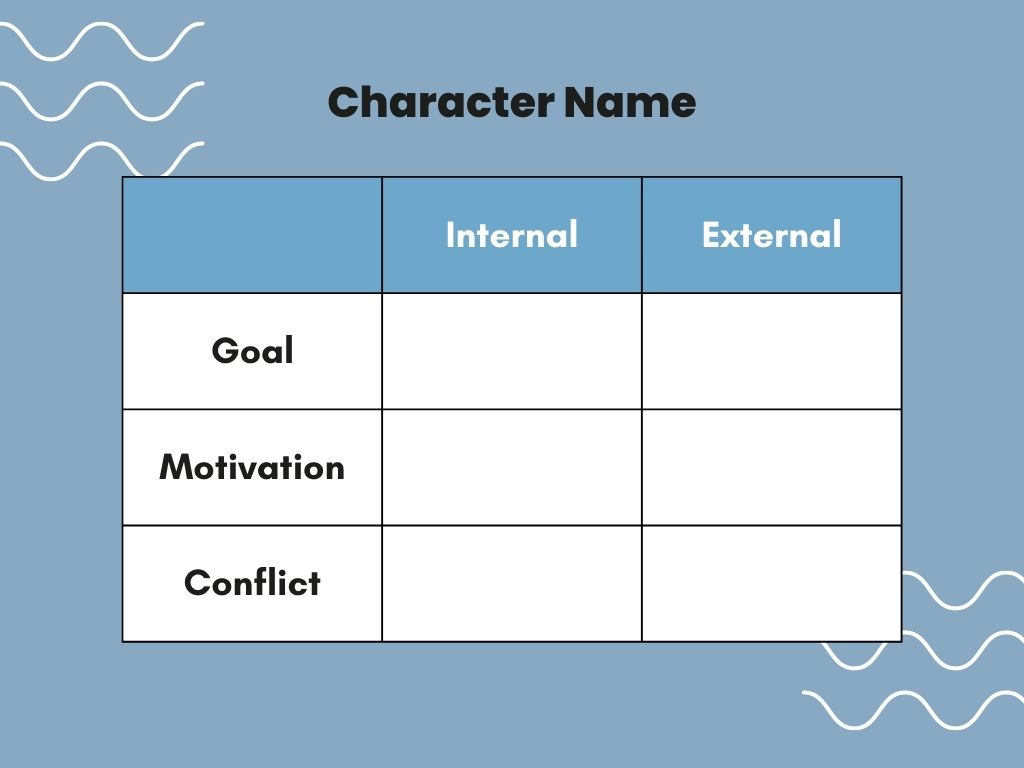

What I loved most about Debra Dixon’s book was it gave me easy GMC charts for stories I knew well. Particularly the ones for Wizard of Oz, one of my favorite movies of all time. I’m pretty sure it would be copyright infringement to share that chart in its entirety here, but the structure is simple:

The very first thing my Pitch Wars mentor requested I do before I revised a single word of my book was to create GMC charts for my main character (the protagonist), the second point of view (the villain love interest), the main character’s best friend, the antagonist, and the secondary (tertiary?) villain (listen, unclear, this book has a lot of villains). Why? Because my arcs weren’t clear. Why? Well, I suspect because even after fifteen years of trauma therapy I still don’t really understand how agency works. Which is how I came to write this blog. But first! An announcement!

Write What You Know, Except…

Here’s where this whole write what you know thing gets a little off the tracks. “Write what you know” was another piece of writing advice that made absolutely no sense to me for most of my adult life. Again, because I interpreted it way too literally. All through my college classes I heard write what you know and bobbed my head while internally I screamed what the ever loving fuck does that mean?

If people only write what they know how do they write about dragons? Or even simpler, how do they write about people they aren’t? Not every character is a self-insert, or should be. Wow that would be… something. Clearly, we are constantly writing what we don’t know. This is terrible advice and yet here it is. Everywhere. All the time.

As I got older and started really writing novels and more specifically, focusing on craft for novels, I realized write what you know doesn’t mean that quite so literally. This might be obvious to some, most even, but it wasn’t to me. It took me years to figure out. Write what you know doesn’t apply to the external, surface level stuff. To plot. To dragons. To if your character likes tomato soup when you like broccoli cheddar (yeah, here I am with the soup again). It applies to the deeper seated things. Write about the human experience unique to you. Your pain. Your joy. Your identities. I also learned (something they did not teach in my writing classes, by the way) it means you shouldn’t write from those deep places you don’t know. The ones that belong to someone else. The stories that are not yours.

This started to make the most sense to me when my internal stories started to bleed onto the page without me realizing. Whole novels I thought were about magic and worldbuilding and friendship and questing. Whoop. Trauma. Whoop. Addiction. Whoop. Secret bisexual. Whoop. ADHD.

That secret bleeding is authentic to the unique experience of the writer. It’s writing what you know. But sometimes, it becomes necessary to trick the system a bit. NOT to usurp someone else’s identity, but to attempt to reclaim your own. And that’s when, in my opinion, the intellectual exercise of a GMC chart can really come in handy for someone with trauma. Because sometimes, you don’t actually know what you know well enough to write it, or to write it with intention and consistency. Or, through no fault of your own, you haven’t learned it. Such is the way with the loss of agency and the first two points of that chart: Goal and Motivation. So, you have to trick your own system (your brain) and write a bit of what you do not know to get to what you do (Conflict).

Goal

External Goal

For brevity (ha!) I know right? I’m going to focus on the main character in this post. But as I noted above, most of your major players should have GMC. Definitely your POV characters and your villain at minimum.

In its simplest form, the goal is the thing the main character wants. In fantasy, what I write, the external goal is usually the thing driving the plot forward. Steal the thing (heist), overthrow the government (coup), save the world (hero’s journey), become the next queen (palace intrigue).

For my Pitch Wars book, the external goal for my main character was “Save her best friend.”

External goals for me have always been a bit easier to figure out, because as I mentioned in my earlier post, having C-PTSD doesn’t stop someone from wanting things. For this one, I would say the advice given is pretty standard. Read widely and see what’s popular. Then give it your own spin. Fantasy stakes are often epic, as I cited, but there’s been a recent demand in the market for character-focused stories. Character-focused stories require character-focused goals. I don’t love saying anything is “overdone” or “dead” (especially as someone who writes fairytale retellings), but I will say a character trying to save the world isn’t always as easy to relate to as a character trying to save their best friend. Or their mom. Or their dog. Now, if their best friend just so happens to be the person most likely to fix the future of the world, well… I mean… you do you.

Internal Goal

The internal goal is what drives the character arc. The character is not always immediately aware of this goal, but you as the author should be. Usually, it’s related to the character’s emotional wound and is the thing that will be healed by the end of the book.

Oop, I used the word healed and hackles across the traumaverse raised. To be clear, your internal goal in a trauma narrative does not have to be (nor would I recommend it be) “heal their trauma.” Nor are character’s emotional wounds limited to one. Indeed, we all have scars aplenty, traumatized or not. When we’re talking about The Emotional Wound and The Internal Goal, we’re talking about the one driving the character arc forward for this one book. Good news for writers is that people are pretty fucked up and have many emotional wounds so loads of internal goals to work toward (meaning more books for that character which for us fantasy authors is key).

On a more serious note, for those of us with trauma, especially C-PTSD, you’ll know “healing” is not a linear journey made up of one thing but a patchwork of unraveling one thing only to realize you’ve unspooled seven others. Followed by fifty more. Which is why I say it’s probably not a great goal for a single book even if we wanted to convey the message that trauma can be healed (which is another post entirely, perhaps for my therapist to address). Regardless of whether you think trauma of that magnitude can ever be healed or should ever be healed, it’s simply too big to do in one book.

For my Pitch Wars book, the internal goal for my main character was to “find self acceptance.” This was related to her emotional wound: abandonment.

Here’s where things start to get a little bit trickier for someone with trauma, in my experience. Internal goals are where character arcs come into play. In theory, if you were plotting the points of your character’s emotional progression over the course of your book, it should look something like this:

First, I’m not a plotter, so part of my issue with *gestures vaguely* some of this, is that. However, some of my issues around internal character arcs are, I’ve discovered, related to trauma. My character arcs never look like arcs. They always look like EKGs. You know, this thing:

This has to do with the difficulty I have as a writer with trauma in understanding a smooth progression of emotion in any situation. The act of healing for me is never linear. It’s always this two steps forward, one step back tango of unraveled mess that doesn’t turn into a nice arc and is also apparently quite frustrating to read to anyone not me. Why? Well, because for most readers it reads as repetitive. “We’ve already done this with this character. Let’s move on.”

Pause. I know this is going to be a long blog. They always are, but it’s because I want to try to address the thousand thousand caveats which I know I can’t do but I can try, damn it.

Is it frustrating to you as a writer with trauma to hear that your authentic story reads as frustrating and repetitive to readers? Absolutely. Does it remain true? Also yes. I again repeat you can ignore every single thing I say in this blog as bogus and do it your own way. You can write the book of your heart about survival with no GMC and an arc that looks like that EKG machine. You can break every single rule in the rulebook. There is no such thing as advice that will lead you to success, nor is there advice you must follow to find it. All that exists is kind of in general information about the current ways stories are told in the United States. There’s information about why some things appear to work and others don’t. There are also examples of people saying fuck off with that, breaking the rules, and everyone loving it. However, for every one of those stories there are ten thousand more who tried the same thing and weren’t lucky. There are also loads of people who follow all the rules and get nowhere. So, I have no magic solutions here, only information.

How does the GMC chart help with the EKG machine effect, then? Well, if you know where you’re headed and what you’re working through, it can be easier to chart a smoother course. Or help you smooth things out in edits, depending on what type of writer you are. Each scene can be approached with an eye for how the emotion is moving forward (and if it could be moving back). Keeping in mind that there are some stutters and one big one (at the Dark Moment) you should have where that emotional wound comes and rears its ugly head, but overall it should be a mostly smooth line toward Aha!

Other craft book recommendations: The Emotional Wound Thesaurus

Motivation

External Motivation

Motivation is all about the why behind the want. Why does your character want the thing? Often, you’ll hear this advice about forming GMC which I quite like: My character wants X [Goal] because Y [motivation] except Z gets in the way [conflict]. Or some variation on this.

Figuring out why your character wants something sounds easy enough, and I guess it can be, but there’s another part of this we don’t talk about often enough and everything about it has to do with agency. If you’re writing a character who’s experienced trauma, the why behind the want has to be stronger than their trauma responses.

The why is what pushes the character forward. In the case of a character with trauma, that means pushing forward through their own trauma, which if you’ve got trauma, you might now be understanding why this is harder for us than other writers, perhaps. Primarily because if you asked me this question, what motivation do you hold now that can make you fight through your own trauma responses? The list is… quite small. And there’s a part of me that is still sitting here saying, “If it’s even possible to do, honestly.” Because some things are just y’know, biological. Burned into my brain and all. I might want to fight through some shit for certain goals, but there are things in my brain that are now wired to not fight. So, it can get murky.

Fortunately, we write fiction, and this is one of those moments where fibbing what you know might be in order. But you probably won’t do it naturally. You will not bleed that experience onto the page like some others. So you have to do it with intention. Via an intellectual exercise like the GMC chart. Why does your character want this thing? And make it big.

For my Pitch Wars book, the external goal of “Save her best friend” was accompanied by the motivation “Because the villain is trying to turn her evil.” Goal worth fighting for and a why big enough to aggressively fight forward.

Keeping that goal in your mind (and your character’s mind) is a good way to keep the plot moving forward. Each scene should be moving either the plot or the character arc (or both) forward. If it’s doing neither, well…

Internal Motivation

Internal motivation is also something I’ll argue is not always known, especially if you’re writing a character who has some trauma. But usually, it relates back to the wound. Why does the character want the internal goal? Well, usually because the wound has left them feeling Some Kind of Way and they’d like to uh… not.

But saying to a trauma survivor “Don’t feel like shit” about something is about as disingenuous as telling them to “Just let it go.” Don’t you hate it? So, once again, we as writers are confronted with the dilemma of needing a why that is strong enough to overcome the trauma to move forward toward the want. With internal motivation, this can all happen sort of under the character’s radar, by the way. They don’t have to seek therapy on the page, though cool if they do.

If you’re writing a romance, or something with a romance subplot, you will likely lean heavily on the love interest for this part, which is helpful. Why does the character want to get over their feel like shit feeling? Well, because it’s affecting this new relationship which could be great. The emotional wound should be something that can be healed with a supportive partner’s love. Another reason it should not be trauma. Because that’s a story no one needs in the world anymore. Trauma cannot be healed by love and if I see another fantasy novel written like… I will stop talking now.

Primarily, however, self-improvement happens inside the self, so your character has to be the one to do the work, with or without a love interest as motivation. Consciously or unconsciously. They might not know exactly what they’re seeking in the beginning, but along the way they should find a reason to keep pushing at the edges of their own capacities, and by the end, they should have found a new status quo.

If they’re fighting trauma, the path is harder. You will likely run into the EKG because creating that smooth arc requires some “letting go.” Sometimes, it might seem unnatural, or “too easy” and that’s because it sort of is. Regardless of whether you have diagnosed, clinical trauma or not, most of us don’t heal anything in a smooth line. Old habits die hard. Old suspicions which are born of old wounds, die harder. It’s almost more natural to write an up and down, back and forth dance than a forward-moving progression. No one ever said writing was easy.

Ultimately, for my Pitch Wars book, my main character’s internal motivation of “find self-acceptance” was accompanied by a motivation of “because she needs it to be free.”

Freedom. What a word.

Conflict

Conflict both external and internal is the “But” that gets in the way. I’m not going to spend a ton of time on it because I think most people writing from a place of trauma are plenty familiar with conflict. In fantasy it’s the villain in the external plot, the things that go wrong, the challenges. In the internal arc it’s those old fears related to the emotional wound creeping back in.

When you’re dealing with trauma, it can often be the thing that stalls the forward motion. The conflict for internal progress of an arc of a traumatized character could actually be the underlying trauma itself. “I want to be more confident because that’s a trait that’s desired in leadership roles but I can’t trust myself because trauma has taught me not to.” That’s pretty much something you could say about me.

The problem with making trauma your conflict is again, that point I made earlier about your motivation needing to be strong enough to overcome it. Am I going to overcome my trauma for work? Doubtful. So two things can be done here. You can revise your goal and motivation to be bigger, or you can revise the conflict to be smaller.

Does that mean you’re writing the trauma out of your narrative? I think that’s a point to be argued. I would say no. Because we do exist in multitudes, and I think you can overcome some internal hurdles without leaping trauma to do so. In my Pitch Wars novel, my main character is not traumatized, at least not in the traditional sense (probably all my characters are traumatized in some way because I write what I know). My villain love interest, however, is.

I didn’t share his GMC chart because some of his goals and motivations are spoilers. But the conflict to his internal motivation is based partly in trauma. Trauma done to him and trauma he’s done to himself. I say partly because it’s only one thread in that spool of so many. By the end of the book, he’s found that one thing he’s been seeking without entirely knowing he was seeking it. What he isn’t is cured or healed of trauma. One piece may be unknotted, but in unknotting that, he’s unraveled more. Arguably, he’s more traumatized. As my therapist says, “With trauma, it gets worse before it gets better.”

Conclusion

When I was studying creative writing, one of my intermediate fiction writing professors put a list of “Rules” on our workshop door. There were 14 of them. Some I remember, some I don’t. Some were standard, some a little more bizarre. We were not to break them in our stories. One was: “Write what you know.” Another: “Use only said and asked.” Another limited us to one exclamation point per ten pages. Yet another said we couldn’t write teenage girls crying in the bathtub. Which never made sense to me, a teenage girl who often cried in the bathtub, trying to write what she knew.

For years, I framed my dorm room and apartment rooms with quotes on writing from the greats. “Don’t tell me the moon is shining; show me the glint of light on broken glass.” ~ Chekhov (who I have a lifelong feud with, doesn’t matter he’s dead). “Your intuition knows what to write, so get out of the way.” ~ Bradbury. “It’s not wise to violate the rules until you know how to observe them.” ~ T.S. Eliot. “Good novels are written by people who are not frightened.” ~ Orwell “Work like hell!” ~ Fitzgerald. “You can make anything by writing.” ~ C.S. Lewis. “A word after a word after a word is power.” ~ Atwood.

I thought these words would inspire me to keep going even when it got hard. What I didn’t realize was I’d surrounded myself with rules I didn’t understand urging me to do things that weren’t achievable for me. My external GMC was this: I want to be a novelist because my voice has been silenced all my life, but I’m too afraid to speak my truth. My internal GMC was this: I want to be courageous because to speak your truth you need to be, but I’m afraid to be punished. Around and around the trauma wheel I went. Wanting to speak to break the cycle. Too afraid to speak because of the damage done by the cycle.

The truth was, I could work like hell, did work like hell, but no amount of working could help me understand. I couldn’t understand the rules to do the things, let alone break them, which meant there were most certainly things I could not create with writing, like a traditional GMC for starters. I sure as shit did not have intuition that knew what it was doing, and as much as I craved power, I was too terrified to seize it were it handed to me on a golden platter which you know, it isn’t.

I’d surrounded myself with words that said I would never be enough. And I believed them.

But here’s the thing: the greats were wrong.

There’s no singular way to write. No rules that can’t be broken, or for that matter, shouldn’t be. Stories aren’t only for the brave or the powerful or the intuitively inclined or the hard workers. Stories are for everyone. But your story, it’s only for you. Which means only you know how best to tell it. If that means self-publishing or going with a small press or popping something up on a blog or never showing a word of your writing to anyone then do it (after the appropriate amount of research and making sure you can afford it and all that comes with it). If it means throwing your heart book about survival that doesn’t follow a single rule at the gates until someone lets you in, then do it (after knowing and accepting if no one lets you in, you are more than your writing). If it means trying a few things to find the right fit, well, you surely wouldn’t be the first of us to wander around for awhile.

The path I ultimately chose was this one. Traditional publishing. Learning the rules no matter how much they confused me so maybe one day I could break them with intention. Telling the greats to fuck off while also remembering they probably did know a thing or two so maybe some of their advice could apply, it just didn’t have to be crushing. Making compromises about how I tell the stories that matter so they’re heard. Hoping one day someone will be able to tell them the way I’d prefer, regardless if that person is me or not. Knowing maybe I’ll be someone who helps pave the way and that can be enough because in so doing, I found my own voice and power, which was the point. This is the path that fits my story and this exact point in my life. I expect it’ll change. I hope it does. Art requires change, in my opinion, and I want to keep producing it.

This post is not to say there’s only One True Way. Because there isn’t. There never was. There never will be. Your story demands your way. No one else’s. This is but a tool and like any other you can choose to use it or find something better or say to hell with all of them and do it your own way. Invent your own tools. Chart your own path.

Whatever you do, though, don’t let anyone tell you they know more about your story than you do.

You are a warrior. A survivor. And you are courageous.

Xoxo,

Aimee